Get the episode transcript here

——-

Marketing ethics, or more specifically, the ethics associated with inclusive marketing doesn’t get talked about nearly enough as it should.

Of course, I’m a big proponent of brands engaging and serving people from underrepresented and underserved communities. But there are times when I wish brands wouldn’t focus on specific communities, and would just leave them alone.

Why? Because in certain instances, brands do more harm than good when engaging with certain underrepresented and underserved communities.

Marketing ethics – or moral principles, as it relates to inclusive marketing, it really boils down to this: do no harm.

That’s it.

Simple to remember — but for some, perhaps not so simple to practice.

5 Marketing Ethics Considerations for Brands Engaging Diverse Customers

Lets break down where most brands struggle with this.

Predatory Practices

In 2008 in the U.S., we experienced a housing crisis – where basically the market crashed. People – myself included lost lots of money when the value of our homes decreased. What was the culprit of this economic crisis that negatively impacted so many people?

Many people say it was the rise of predatory mortgage lending.

Investopedia describes predatory lending this way:

“Predatory lending puts many borrowers at risk, but it primarily targets those with few credit options or who are vulnerable in other ways—people whose inadequate income leads to regular and urgent needs for cash to make ends meet, those with low credit scores, those with less access to education, or those subject to discriminatory lending practices because of their race, ethnicity, age, or disability.”

David K. Musto, is a finance professor at the Wharton School of Business. He’s also co-author of the paper, Predatory Lending in a Rational World, described predatory lending this way:

“I make a loan to you that reduces your expected welfare.”

And that’s really at the heart of predatory marketing practices. The impact is particularly felt by people who are part of underrepresented and underserved communities.

It is unethical and predatory for brands to specifically target marginalized communities with products, services, and experiences that “reduces their expected welfare.”

Governments and plenty of organizations recognize the harm that predatory practices and predatory marketing can cause.

That’s why in the U.S. the FTC has issued guidelines that regulates and restricts marketing to children under age 13. They know the harm deceptive marketing could cause them.

Children are a protected group from predatory marketing. But unfortunately, lots of adults and communities who are already vulnerable are the target of this type of marketing. And it reduces their expected welfare.

Research shows that alcohol availability and advertising is disproportionately concentrated in racial and ethnic minority communities.

One article in Medical News Today showed results of data that highlighted the following:

- Research shows a growing disparity between ads aimed at marginalized groups versus their white peers

- Fast-food restaurants such as McDonald’s, Domino’s, and Taco Bell spent over $1.5 billion on TV ads in 2019 to target Black and Hispanic kids

- In 2019, Black youth viewed 75% more fast-food ads than their white peers, while no healthy items were promoted on Spanish-language TV

The article also highlights a growing body of evidence that has found a strong link between obesity rates in children, and an increase in advertising of less nutritious foods, including fast food.

In Chiapas – Mexico’s southernmost and poorest state, consumption of Coke products and other sugary drinks are highest in the world. A 2019 study by the Chiapas and Southern Border Multidisciplinary Research Center (Cimsur), found that residents of Chiapas, drinks on average 2.2 liters of soda a day. That data includes both adults and children.

Marketing works.

And because it works, brands and marketers have an immense amount of power.

And with that power comes a tremendous responsibility to operate ethically. Marketers should not engage in practices that will “reduce their expected welfare” of the people they are targeting.

This is especially important when engaging with communities that are already vulnerable due to systemic and societal forces.

Marketing ethics means not engaging in the unethical practice of preying on vulnerable communities. Do not specifically promote products to them that will not leave them better off than the way you found them.

Cultural Appropriation

We can’t have a conversation about marketing ethics and inclusive marketing, without covering cultural appropriation.

I did an entire episode on cultural appropriation on the Inclusion & Marketing podcast, if you want to dig even deeper into the topic.

Here’s one definition of cultural appropriation:

The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of customs, practices, and ideas of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.

Basically – cultural appropriation is taking something that has deep rooted history, tradition, and meaning in one culture, and then using it for your own benefit – without ever acknowledging or providing royalties to the communities it originated from.

In my book, cultural appropriation is just plain stealing.

It is not ok from a marketing ethics standpoint.

We’ve seen a lot of cultural appropriation in fashion over the years.

A few years ago, the Secretary of Culture of Mexico sent a message to fashion brands Zara, Anthropology, and Patowl – claiming some of their designs used patterns from some of their indigenous groups in Oaxaca.

The Minister asked for a “public explanation on what basis it could privatise collective property.” The Mexico culture ministry called for the brands to award benefits the brands gained from using those designs, to be awarded to the communities behind them.

Let’s talk about a different kind of appropriation that is more common – but can still cause harm.

There’s the use of AAVE – African American Vernacular English, that many brands engage in. AAVE is a common way Black people in the US communicate with each other in their everyday conversation.

Part of the challenge, is that Black people, are often shamed, or even denied opportunities for using AAVE. This is true in many cases of cultural appropriation. People are shunned and ridiculed for embracing and using parts of their culture.

Black people who use AAVE are often viewed as unprofessional or even intellectually inferior for using it. But those same activities or cultural elements are viewed as “trendy” when people from dominant cultures latch on to it.

AAVE is one of those things.

The Linguistics Society of America issued a statement on AAVE, defending its use and legitimacy by African Americans. Here’s part of what they wrote:

“the systematic and expressive nature of the grammar and pronunciation patterns of the African American vernacular has been established by numerous scientific studies over the past thirty years. Characterizations of AAVE as ‘slang,’ ‘mutant,’ ‘lazy,’ ‘defective,’ ‘ungrammatical,’ or ‘broken English’ are incorrect.”

Ok – so let’s get to the appropriation part.

Now we’re seeing a proliferation of non-Black people and even brands using AAVE. Of course, these uses come without acknowledging it’s origins, particularly the Black community, and the Black Queer community. Non-Black people and brands do not receiving any of the negative associations or consequences that come with using AAVE.

Here’s how Nikki Lane, an assistant professor at Spellman College described how hearing non-Black people using AAVE makes her feel:

“You care about what we say, you’re interested in how we speak, you’re interested in taking things from us, because language is cultural production. It’s something that Black folks create together. So you’ll take that, but you won’t take us.”

When brands and non-Black people use AAVE without crediting Black people or the origins of the term, it causes harm. It is a form of erasure of the contributions of Black people to the culture.

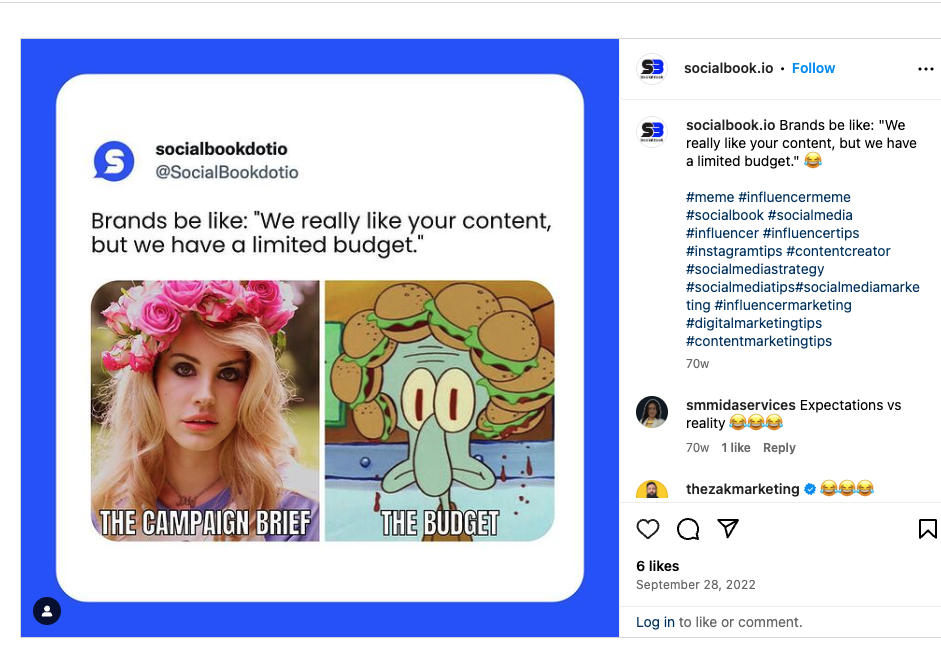

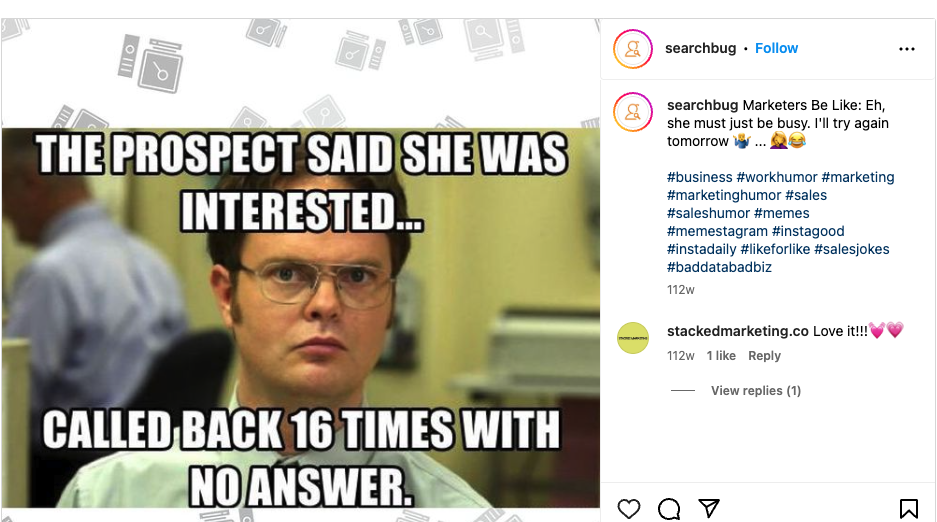

The “be like” meme commonly used on social media, is a form of appropriating AAVE.

I’ve seen a variation of this meme countless times on social:

This blog post from Writer’s Room has a detailed description of the origin of “be like”. It also has 5 other AAVE terms brands are using, such as “it’s giving” and “tea” in the show notes for you.

Let’s avoid appropriation in all its forms.

Extraction

Extraction is a big problem when it comes to inclusive marketing. It comes from a place where brands are acting in a manner that focuses fully on their own financial interests. And that financial focus happens at the expense of people.

Extraction comes as an marketing ethics concern, because it causes harm to already vulnerable communities.

I covered this topic more in depth on the Inclusion & Marketing podcast in episode 14.

That’s really what extraction is in this context. You are only taking from the underrepresented and underserved communities. And doing nothing outside of your products and services to give to them.

You might say, “well Sonia, as a brand, our products and services are how we give to the communities we’re serving. Why should we do anything different for underrepresented and underserved communities – what’s wrong with that?”

Let’s walk through why extraction only is problematic.

Let’s replace in this illustration underrepresented and underserved communities for vulnerable communities.

A brand that is purely taking from vulnerable people for capital gain feels unfair and super selfish.

Here’s a real life example.

Each year during Pride month, there are a slew of brands who paint their logos with the rainbow. Many even offer limited edition Pride products.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of brands that are doing this for the purpose of extraction. They do it to make money off of the LGBTQ+ community and their allies. They don’t actually care about them and their well being.

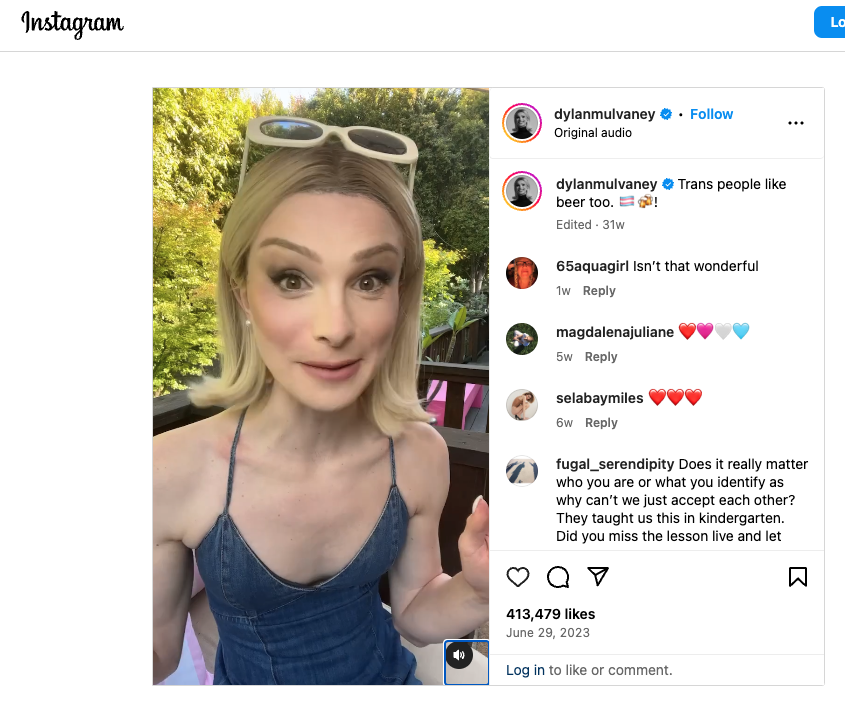

In 2023 Bud Light got a ton of backlash from the influencer promotion they did with transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney. The Bud Light team sent her a can of Bud Light with her face on it. Dylan briefly showed the can in a sponsored video she posted on her socials.

As a result, some Bud Light customers started boycotting the brand, and throwing out their Bud Light. Some of them even spewed hateful comments to Dylan and the transgender community.

Months later, Dylan posted a video that addressed what happened to her as a result of that Bud Light mention:

“”[W]hat transpired from that video was more bullying and transphobia than I could have ever imagined. And I should have made this video months ago, but I didn’t,” – the reason why, Mulvaney said she was scared.

Dylan went on to add that she waited for things to get better, but “But surprise! They haven’t really. And I was waiting for the brand to reach out to me, but they never did.”

Bud Light never reached out to Mulvaney.

So did Bud Light do the ad because they actually care about the LGBTQ+ community? Did the brand want to include the community and and have them see themselves represented?

Or did the brand do it just so more of the LGBTQ+ community would buy Bud Light?

Their actions in response to the negative reaction from some of their customers signals that extraction was really their objective.

They couldn’t even be bothered to check in on Dylan privately to see how she was doing. They didn’t do or say anything to attempt to shut down the transphobia, threats, and bullying.

Fran Tirado is a writer, editor, and community maker for all things Queer. Back in 2019, Fran posted this fantastic thread. It really captured the heart of how brands “extract” from the LGBTQ+ community during Pride month:

Extraction from a vulnerable community for your own gain without giving anything of significance back to them is harmful. It is something you shouldn’t do from an marketing ethics standpoint.

Perpetuating negative stereotypes

Sometimes when underrepresented and underserved communities finally are represented, it is in a way that causes more harm than good.

I did an episode early on in the Inclusion & Marketing podcast, with Gelaine Santiago. In it, she talked about the little representation she saw of Asian women when she was growing up – and when she did, she often found that it was a “silent friend” on the sidelines.

To her as an young impressionable Asian girl, only seeing herself portrayed on tv and in movies as the silent friend, made it feel like people like her didn’t have a voice.

I loved my chat with Gelaine, so go have a listen if you already haven’t – it’s episode 9.

I’ve seen a number of commercials that perpetuate the narrative stereotype of “the angry Black woman” or that only present a limited narrative of beauty.

Gender stereotypes run rampant in advertising as well.

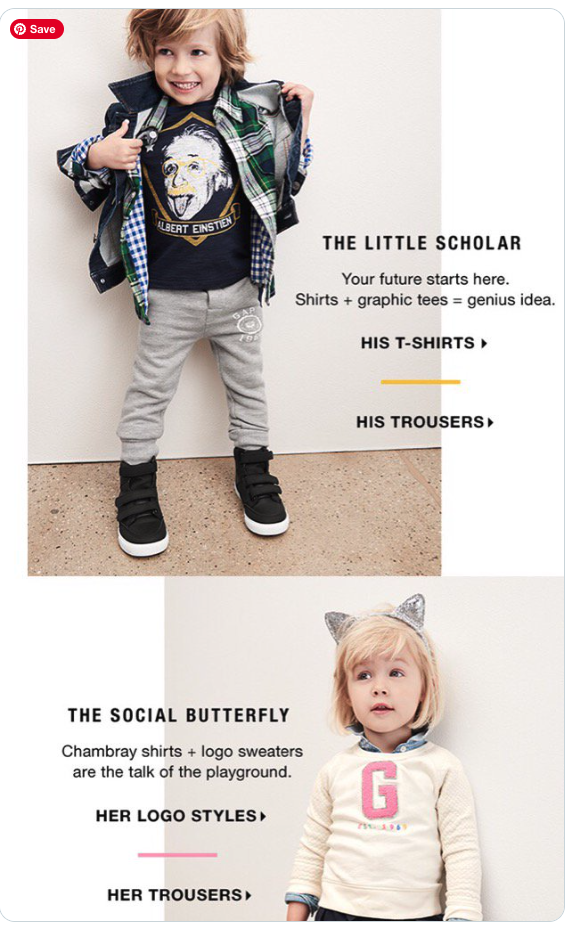

A Gap ad in the UK came under fire a while back for perpetuating gender stereotypes with kids. In one campaign that received a lot of complaints, a little boy is wearing a graphic tee that says “The little scholar: your future starts here. Shirts + graphic tees = genius idea.” And then the image of the little girl says “The Social Butterfly: Chambray shirts + logo sweaters are the talk of the playground.”

The UK takes harmful narratives of gender stereotypes seriously, and has even issued a ban on them by the Advertising Standards Authority, known as the ASA.

The ASA says that they implemented the ban because they found evidence that harmful stereotypes “restrict the choices, aspirations and opportunities of children, young people and adults and these stereotypes can be reinforced by some advertising, which plays a part in unequal gender outcomes.”

ASA Chief Executive Guy Parker stated that, “our evidence shows how harmful gender stereotypes in ads can contribute to inequality in society, with costs for all of us. Put simply, we found that some portrayals in ads can, over time, play a part in limiting people’s potential.”

Now the UK has data on gender stereotypes and the harm it causes – and I’d venture to say that harmful stereotypes and narratives across the board cause harm.

And as marketers and business leaders, we have a moral responsibility from a marketing ethics perspective to not perpetuate these stereotypes and cause further harm to individuals and society on the whole.

Performative – bait & switch

Nobody likes a bait and switch. But often enough, that’s what happens when brands present as if they are one thing, when they actually aren’t.

Me and Jonathan were watching a docuseries on Netflix recently where someone explained that in many instances, when eggs are labeled “cage free” it doesn’t mean what most people think.

In a lot of instances, it doesn’t mean that the chickens were roaming free happy on a farm somewhere. But rather they were in a battery cage that is 67 square inches, or as one source – The Human League, says amounts to about the area of a piece of lined paper.

When I heard that, I felt duped. I thought I was buying one thing, but turns out, the way it was promoted was nothing like the reality.

There are other examples of brands being performative – which exists in both activism and marketing. Like in examples of greenwashing, where a brand will tout its commitment to the environment, or the strides they are making and the donations they are giving to environmentally focused charities, as a way to convince and persuade consumers that they are sustainable and helping the environment.

They do this and promote they are “green” in their marketing, when actually, their practices are doing more harm than good.

Volkswagon was accused of this some years back. The brand admitted to fitting their cars, including the Beetle, Jetta, and Golf with software designed to give false readings on emissions tests, so it would pass them.

Here’s how one writer and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania described the scandal:

The “cheating cars,” as they are called in Alexander and Schwandt’s paper in The Review of Economic Studies, were first sold in the U.S. in 2008. They were touted as an environmentally conscious choice and earned awards such as “Green Car of the Year.” Later investigations, however, found the cars’ software-activated emissions controls worked only under testing conditions. On the road, these controls were disabled and the cars generated high levels of particulate matter and gases that are known to worsen lung function, exacerbate asthma and heart disease, and create smog.

Brands do this kind of bait and switch when it comes to inclusive marketing as well – and it happens even when there isn’t mal-intent.

But intention is not the marker of success, it is the impact it has on the consumer and communities.

Last year I came across a post on LinkedIn from the lovely Lola Bakare – who was a guest on this show on episode 72 on the Inclusion & Marketing podcast.

In the post, Lola is calling out a brand that she loves and supports, Canva – for their use of what appears to be performative stock photography:

To be clear, I’m not ok with this from a marketing ethics perspective. On this particular post, Zach Kitschke, Canva’s CMO responded in a loving way with a commitment to do better, which Lola remarked about on her post.

But here’s the gist of it – in your quest to showcase more diverse visual imagery, the imagery needs to be true and representative of what people will actually find when they engage and interact with your brand.

If your goal is to showcase the diversity of your company, and you include a picture of the one Black woman on your team in all your promotional materials, and then someone comes and joins your company and finds out it isn’t diverse at all, that’s bait and switch.

If you put photos up – stock or not, that make it seem like your customer base, your event, or your team is diverse, and it really isn’t anywhere close to being representative, rethink that as being performative.

Bait and switch. Performative marketing.

Not where we want to be from a marketing ethics perspective when it comes to inclusive marketing.

Present accurate narratives of what exists in your business. Today. It’s totally ok to talk about where you want to go in the future.

But be honest and transparent about where you are today. Do not mislead people into thinking you are something you are not. Do not mislead people into thinking you are more inclusive than you actually are.

So what’s the bottom line here with the whole bait & switch, performative marketing thing: don’t do it.

How to Infuse These Marketing Ethics Principles Into Your Marketing

OK – we covered A LOT in this episode, but we needed to.

There are plenty of marketing ethics considerations associated with inclusive marketing. I wanted to make sure you were thinking about this.

How do you avoid doing things that are unethical as you work to engage people from underrepresented and underserved communities?

Keep these two questions at the forefront of your mind, your thinking, and your actions.

First off:

Does what I’m doing leave the consumer/customer better off than the way I found them?

And the second one is very similar to it, but it expands the context:

Does what I’m doing leave the consumer/customer’s community better off than the way I found them?

As you are asking these questions — go through the exercise of evaluating if there are ways in which what you want to do, are doing, or planning to do will cause harm.

Ask yourself, will the campaign, the products, services, and experiences you deliver to this vulnerable community — reduce their expected welfare.

This is also why it is super important to have a diverse and representative team that has people with the lived experiences from the communities you want to serve.

If you aren’t part of these communities, it is likely that it may be even more difficult for you to identify ways in which something could cause harm.

Cultural intelligence is critical.

Not being aware of how something could cause harm doesn’t prevent the harm from occuring.

So as inclusive marketers, let’s be in the harm prevention business.

It’s the ethical thing to do.